An eerie WWII underwater graveyard of ships still holds the remains of Japanese servicemen

Some 1,100 miles north-east of New Guinea lies an atoll, gently tucked in by the Pacific Ocean and more or less secluded from the rest of the world.

It’s called Truk (or Chuuk) Lagoon, part of the Pacific archipelago-state of Micronesia. Truk Lagoon was first sighted by a Spanish expedition in 1528. At the time, the lagoon was home to several indigenous tribes who lived in total isolation.

Centuries passed and Spain, the initial “owner” of Truk Lagoon lost its position in the Pacific after the Spanish-American War of 1898. The Spaniards were forced to sell the entire atoll to the Germans the following year. Once again, in the aftermath of the First World War, the lagoon changed hands, becoming the property of Japan.

By World War II the Japanese had established a port and a naval stronghold, which was manned by a total of 40,000 soldiers. The atoll itself includes a natural harbor enclosed within a protective reef, making it ideal for strategic purposes.

This was one of the main reasons why the Empire of Japan decided to use the lagoon as a base for operations in the Pacific. The surrounding islands were installed with roads, trenches, and most importantly coastal gun batteries and mortar emplacements.

This was a preliminary protective ring for the atoll which at one point held the majority of the Japanese fleet. Some of its biggest and most important assets, including the largest battleships ever built ― the Imperial Japanese Navy’s Yamato and her sister ship Musashi — were moored here.

Japanese military infrastructure at Truk Lagoon included five airstrips, seaplane bases, a torpedo boat station, submarine repair shops, a communications center and a radar station. It was the largest Japanese forward naval base, comparable in size and significance to Pearl Harbor.

Ironically in 1944, it suffered a fate similar to that of the infamous U.S. military port attack which marked the beginning of American involvement in WWII. Following a large-scale naval aerial assault, the Japanese lost a portion of their fleet at Truk Lagoon, rendering it useless for further strategic operations.

Despite managing to evacuate their heavy cruisers and aircraft carriers just in time to avoid the slaughter which took place on February 17, 1944, and lasted for three consecutive days, the Japanese Imperial Navy was never able to fully recover from the blow.

The death toll was high ― 12 small light cruisers, destroyers, and auxiliaries, together with 32 merchant ships that happened to be stationed at the Truk Lagoon. Along with the ships, around 275 Japanese aircraft were shot down. Together with the ships and the aircraft, some 4,500 men lost their lives during the raids which were designated as Operation Hailstone.

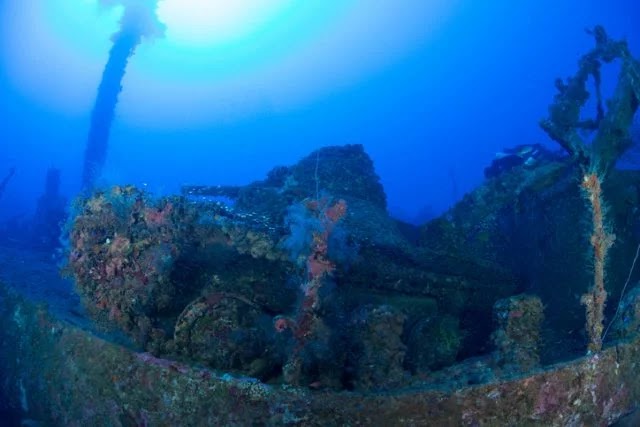

In 1969, French oceanographer and filmmaker Jacques Cousteau followed the trail of the once mighty fleet stationed in the Truk Lagoon and discovered a huge graveyard of ships and equipment which laid untouched on the seabed since the day of the attack. This led to the production of an episode within Cousteau’s documentary series, titled The Lagoon of Lost Ships.

Together with ships, downed aircraft and even tanks, French divers found a great number of human bones resting on the bottom of the lagoon. An eerie sight reminded the surprised visitors that this was once indeed a place of fierce battle.

Cousteau’s discovery sparked huge interest among other diving clubs, adventurers, and explorers, but it also attracted the attention of the Japanese government, who launched an operation to excavate the bodies of their fallen sailors, soldiers and pilots in an effort to provide them a proper burial. In the meantime, the whole site has been classified as a Japanese war grave.

In The Lagoon of Lost Ships Jacques Cousteau observes the wreckage on the seabed, as he poetically narrates the documentary’s ending:

“Truk Lagoon presents a mysterious planet of life and death. On the one hand, nature absorbs the artifacts of war. And on the other, she has preserved them. Only centuries from now, will every trace of man’s follies vanish from the bottom of Truk Lagoon.”

So many intact ships lay scattered in such close proximity attracts divers from all over the world. Since the days of the battle, the ships, along with other equipment have remained more or less in the same position in which they sank. Wrecks that are up to 50 feet deep can be seen from the surface, as the water in these parts is extremely clear.

On one of them, traces of a torpedo impact can be seen clearly. Another, identified as the medium coastal freighter Gosei Maru has a huge hole on its deck, indicating that an aerial bomb was dropped directly above it.

The identification of ships in the Truk Lagoon has become an obsession for many enthusiasts who stop at nothing when it comes to detective work and history. Other relics like motorcycles, radios, weapons, spare parts, and railroad cars can still be found at the bottom. Diving expeditions are now a common activity in the lagoon.

In 1972, the lagoon was recognized as a historical site and designated as the Truk Lagoon National Monument. This was an important step for protecting the lagoon from looters and raiders, but consequently, it also raised awareness on the effect the wreckages have on the environment.

Fuel and oil which went down with the ships have been polluting the lagoon for decades. In 2011, an oil spill presumably coming from one of several Japanese tankers sunk in 1944 occurred, endangering the diverse array of marine life which resides in the wrecks.

Environmentalists claim that it is an urgent issue which, if not dealt with, could cause further harm to both the site and its current inhabitants like manta rays, turtles, sharks, and corals.

No comments